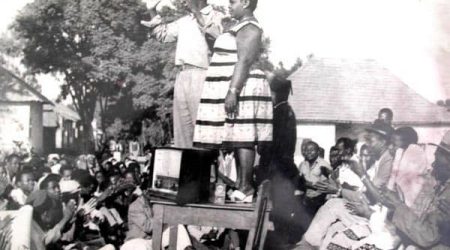

Three generations of women Beggars

MY NAME IS TUMAINI. My mother called me Tumaini, Hope, thinking that my birth would improve her lot in life. It did not! All members of my family are beggars. My two aunts; my cousin Wema; my little brother Nyau; and all our friends here in Dar es Salaam are beggars. We survive by begging in the streets, and then share the food bought by money which we obtained from begging.

In fact, my grandmother is also a beggar, who came to Dar es Salaam from Dodoma, after her husband died, and the patch of maize farm which provided sustenance for her family was taken away by her brothers in law. So my grandmother left Ihumwa in Dodoma, with her 3 daughters who included my mother and came to Dar es Salaam by hitching lifts from lorry drivers who transport maize and water melons from Dodoma to Dar es Salaam.

I was born when my mother was 14 years of age. She had been lured by a shopkeeper in the city center into his shop, after he promised her he would give her TZS 5,000, by saying he was not carrying any money with him when she had stopped him and begged for charity. In the shop, which was dark and full of boxes, he raped her then threw her out of the shop with the warning not to go near him again, otherwise, he would inform the police that she is involved in prostitution.

I do not know another way of life as my beggar mother used to sling me on her back with a piece of kanga rag and go on streets to beg when I was a baby. When I could walk, I too became a beggar.

I have never been to school although I am now 12 years of age. My job is to hold my grandmother’s hand while she pretends to be blind and we plow the streets of the busy thoroughfares of Dar es Salaam, begging for alms from people in cars. We have learnt to spot the people who would take pity on an elderly ‘blind’ woman and her little granddaughter- I look small, younger than my age- then my grandmother would hold out her gnarled hands and beg for money. Usually, it is women, the smart women in their cars, who hurriedly hand over coins or a TZS 500 note to my grandmother. I suspect the women hand over the alms out of guilt, the guilt which comes from being well off financially, then seeing an elderly ‘blind’ woman being led by her granddaughter to beg for coins to buy food.

Actually, we have become quite adept at crossing busy highways and also in the voices we use to beg. Begging is an art. One has to know the time when the wealthy people leave their offices to go home; or when the wealthy women go shopping; or when the foreigners are out in the streets, doing sightseeing. That is when we go out ‘to work’. On a good day, we earn TZS 10,000-14,000. On a bad day, particularly when the weather is bad and raining, we ‘earn’ less than TZS 5,000.

We do not have a house. We usually sleep on pavements and when it rains, we take refuge in shop fronts. The watchmen guarding the shops sometimes take away our ‘earnings’. They often ask my mother; aunts; and I; have sex with them in lieu of shelter in the spaces which they are employed as watchmen.

I have seen girls of my age wearing school uniforms and carrying school bags while on their way to school. I have seen girls who live in houses. I have seen girls whose mothers hold their hands while crossing the streets. With me, it is different. I, have to hold the hand my elderly grandmother who has to act blind so that people would take pity on us and give us alms.

My brother Nyau was born when I was 5 years of age. He is called Nyau- Alley Cat because he can weave his way in and out, and around fast moving cars, to beg for coins from the people in cars. I keep telling my mother that Nyau should be sent to school and study, and grow up to be a gentleman, like the men we see holding bags, wearing smart suits, and looking respectable.

My mother is afraid to approach education authorities. In fact, she is afraid of all sorts of authority figures. She has trained Nyau, my cousin Wema, and I, to spot a policeman from a distance, and ways of dodging so that we do not get caught for pestering people in the streets. My mother’s sister Semeni has a policeman boyfriend who told us that we could be charged with loitering in the streets, and with stalking the people from whom we beg for money.

My Aunt Semeni is also a beggar although she sometimes disappears for days, and when she gets a boyfriend who would pay for a room for her in a guest house, our lives get better for a while. When that happens, we get to sleep in the room and eat the scraps of food left over by guests in the guest house, until Aunt Semeni is dumped by the boyfriend and we go back to sleeping in streets.

My mother talks of renting a room where we would all stay together but she can never lift herself from the apathy in which she is immersed and we remain what we are, Street People, living; working; sleeping; giving birth; and dying; in the streets.

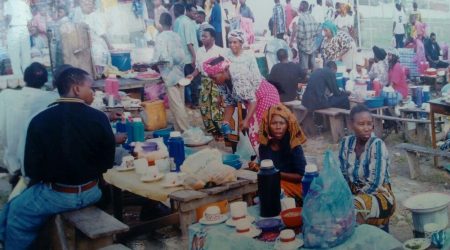

I once tried my hand at working as a domestic maid but the lady who employed me was very strict. She wanted me to take a bath everday, and also told me not to invite my family members into her house. She said “beggars tend to be thieves” which was so unfair, because we are not thieves. We are beggars. Our trade is to beg for money from people in the streets and that is how we survive. Society calls us “Omba, Omba” – beggars- which is fine with us. Everyone has to have a description for the work they do. There are the “Machinga”, who traipse all over the city selling all sorts of goods; there is the nurse who gives us injections when we get malaria; there are the ‘Dada Poa’, the ones who sell sex; they are quite nice to us. They give us coins, and sometimes food like chips. I love chips. Everyone has to have a trade. Ours is begging.

In the city, each family or group of beggars has a turf, a terrain. Beggars also have varying modus operandi while plying the begging trade. For example, there are the beggars on wheel chairs who shunt across Samora Avenue; then across Indira Gandhi Street; Azikiwe Street; then back to Samora Avenue. These beggars on wheel chairs, who have physical challenges, (although some of them pretend they have physical challenges like my grandmother), tend to be police informers, so we steer clear of them.

There is one elderly man whose legs are deformed who drives a tricycle when he goes begging. The tricycle does not have feet pedals but moves with some gears operated by hand. This man whom we call Babu, has a foul mouth, and he uses that foul mouth as a weapon. No other beggar dares to cross into his ‘territory’ which is around Morogoro Road, starting from the city center, to Magomeni. I sometimes allow him to fondle my breasts and he allows Nyau and I to do begging in his territory.

We, my family, keep all our belongings in boxes and a tattered suitcase which my Aunt Semeni had been gifted by a boyfriend. When we ‘go out to work’, one of us stays behind, in the shade to keep guard over our belongins. Sometimes, we leave our possessions with a friendly shopkeeper who keeps them in his shop until we return in the evening from begging. In exchange, we would give news to the shopkeeper about his rivals down the road.

We carry our money on us. We have a rota system whereby, my mother and my two aunts share the saucepans. The chicken sellers sometimes sell the offal, the chicken tripe to us, sometimes, they give us the heads and feet of chicken for free which my mother or one of my aunts cooks and we eat the food with ugali.

I have 2 dresses. One was given to me by an Indian lady, the wife of the friendly shopkeeper, which is rather large but very pretty, decorated with embroidery and glass beads. I keep this dress for special occasions. We do celebrate, sometimes. The other dress was given to me by the lady who had employed me for 3 weeks as a domestic maid. I usually wear this dress, made from kitenge cloth when I have to go to hospital for treatment. We get ill all the time. Malaria; and stomach disease; and worms; and lice bother us. You see, life on the streets can be tough, but am used to it. Those 3 weeks when I worked as a domestic maid and when I was given a bed; clean bedsheets; a mosquito net; and 3 meals a day made me realise that the others, I mean people who are not beggars, live differently from us.

We rarely take a bath, instead, we wash our faces at a tap in a petrol station. We are used to washing our faces and brushing our teeth in public. I got to know about tooth brush from the lady who had employed me.

My mother is pregnant again. She also has HIV which she found out when she had to go to the clinic. The doctor has given her medicine which she has to take everyday. I’m very worried about my mother. She is losing weight and can no longer go out to beg. Besides, when people see a pregnant beggar, they do not take kindly to her. They tell her to get the man who made her pregnant to provide for her.

My grandmother is old now. She is tired of walking all day, pretending to be blind while begging. She talks about going back to Ihuma to die among her people. I get very agitated when my grandmother talks about death. I also keep telling her that “we are your people, your family”. I have never been to Ihuma but I hear that people there think everyone in Dar es Salaam is rich.

There are raids every now and then when beggars in the city are rounded up and sent back to their natal villages. We have learnt to sniff the imminent raids and we hide until the operation is over.

Sometimes, I look into houses through windows and I see families which are settled; living normal, safe lives; without fear of rain, or police raids; and I feel sad. I sometimes wish Nyau; my mother; my grandmother; my aunts and their children; could be like those people I see in houses when I peer in the windows.

I know I would never get the chance to lead that kind of life, but I wish Nyau would be sent to school; be able to read the newspaper; get a job, maybe as a driver; be settled. I so much wish my brother would lead that kind of life.

I have to take care of my mother now. I also have to take care of my grandmother. I worry about Nyau, that he might get caught pilfering fruit from a cart and get sent to the children’s detention center. Molo, Nyau’s friend was caught trying to steal a tyre from a parked car which they did not know could talk. When they touched the car, it shouted, and Molo got caught and was sent to the children’s detention center.

I worry all the time…….but I believe that we should be given a chance in life. After my mother has the baby, I want her to register Nyau in school. I also feel I should get a job again. I have to take care of my mother and grandmother……..

This testimony was given to the writer by a young girl from a family of beggars.We need to look at beggars with different eyes, not as a scourge on society, scum by some peoples’ definition, but as human beings who got transplanted from their natal homes by poverty; drought and lack of food security; patriarchy; insufficient infrastructure to accommodate their needs.

“Together We Can Make it Happen”

Leila Sheikh

Comments (4)

So touching story, some challenges havr to be solved first to make beggers stay at their home.

Yes Sophia.

We need a collective Decision for opportunity and economic justice.

Leila

So touching. No human being with a normal heart can read this article to the last sentence without being emotional. It is not only factual but alsi very sincere. Much as i have never been indifferent to those in need including beggars on our streets but this piece has left me wanting to get an answer to the basic question are beggars not from among us? Why do we allow part of us to go begging amid this enviroment of plenty everything. Have we lost our sense of humanity or we have become inhuman.

Can someone get Nyau enrolled in school so that some of us can pay alms by paying for his school fees?

Yes Dr Shoo.

It is indeed sad.